After completing his Master of Architecture (RIBA Part II) at the University of Westminster, 3D printing bureau, Lee 3D, commissioned Bryan Ratzlaff to write Digital Craft. The book focuses on the relationship between the architect, the model and the 3D printer and in this article, adapted from the study, Bryan, now of SPPARC Architecture, talks us through the importance colour plays in 3D printed architectural models.

Beyond the fact that a 3D printed model’s materiality differs from that of a traditionally crafted one, architects can exploit the technology to have a discernable effect on other physical details and qualities of appearance. Combining the capabilities of both a modelling software and a 3D printer, models can easily be coloured, texture mapped, incorporate any physical texture, include minute details and be tailored for printing at any scale.

Many of these qualities are an extension of the basic geometry being more accurate since a model is composed of a single object rather than a sum of parts. This means each face of geometry will be exactly where it should be and should multiple models be required to fit together; tolerances can be designed into the objects that will allow a perfect fit.

Advantages of the technology’s accuracy also extend to the data set of a project as a whole. Models can be built at a particular scale and will precisely match a drawing printed at the same scale. This can also be advantageous in instances where digital information is projected onto the physical object.

The independent information resource and discussion forum focused on London's built environment; New London Architecture (NLA), has taken advantage of this trait with their newly digitally produced London model. According to NLA Chairman, Peter Murray this model, ‘is so much more accurate than the previous hand built model, that we can outlay Ordinance Survey data just by taking it straight from OS drawings and we just project it on, and it is millimetre accurate.’

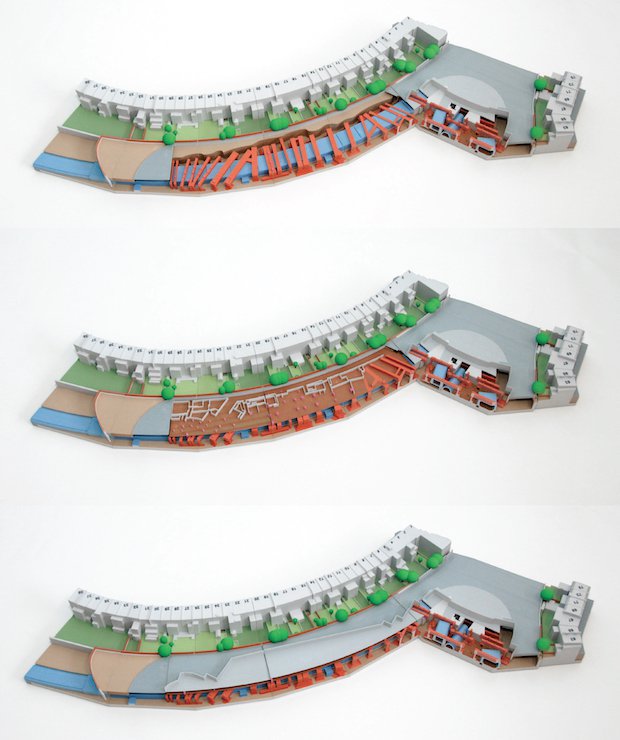

The use of colour in 3D printing can increase levels of realism and create options for representing information that would otherwise be difficult to communicate with an object fabricated from a single material. Used in a similar fashion to a multi-medium traditional model, colour has the ability to convey a range of architectural information and imply materiality.

While machines with inkjet powder technology can print effectively any colour, many architects also make use of the range of greys that can be printed to emphasise spatial qualities or delineate specific information about a project.

Aside from communicating architectural information, the use of colour is also an effective technique to imply a range of materiality in the object itself. As is common with traditionally crafted models, differentiating the base of model can have a desirable effect on the aesthetics of the object. Consisting of a single material, a stand-alone 3D printed model requires the use of colour if this or other material effects are desired. Again, the use of greys can be particularly useful in this manner, as they also retain a level of neutrality that is often desired by architects.

Despite the ability for 3D printing to easily create coloured models, colour remains a challenging feature to correctly translate on a model. This issue of expressing accurate colour, perhaps, is exacerbated with 3D printing, due to some technical variables within the technology.

First, there are hardware considerations that need to be understood – primarily print head alignment on an ink-jet 3D printer – for the printer to achieve consistent colour results. Furthermore, achieving a colour match for the desired colour can be difficult; the machine’s ultimate output uses a CMYK process, whereas many digital modelling programs primarily handle colour in RGB, and the colour samples that architects attempt to match are likely to be in RAL or Pantone colour systems.

To aid conversions between colour codes and the printed output, 3D printing bureaux and modelmakers can create a range of colour samples upon which accuracy tests can quickly be based. Despite the possibility of accurate colour, many architects shy away from its use. According to Senior Associate Partner at PLP Architecture, Neil Merryweather, ‘colour is so emotive and so risky to get right, it is just not practical’ for regular use in practice.

The difficulty of using colour in architectural models helps to introduce one of the more obvious and identifiable physical characteristics of a 3D printed model: literally how it looks. Whether it is the difficulty in matching colours or the architect’s desire for neutral models, the 3D printed model has become well associated with the colour white. Further embellishing this neutrality is the fact that entire models are made out of a single material, compared to models crafted in more primitive materials, where an additional medium could visually separate a base or detail.

These limitations of the technology are what form the requirement for computer modelling to be creative, maximising the visual purpose of the model.

Although this trend of monochrome 3D printed models may imply a lack of creative input to their style, it could be argued that architects have in fact converged upon a conventional aesthetic. Evidence of this can be seen in the way architects have drifted away from the full-colour model samples used to sell the technology to them in the first place.

The vision of the Z Corporation engineers that created the full-colour ink-jet 3D printing technology was one where the machines would be used to their fullest capabilities, producing colourful, realistic models. However, architects have long had a tendency to refrain from this kind of modelling, preferring a ‘less is more’ aesthetic. As Peter Murray notes, ‘totally realistic models have to be done very carefully. Otherwise they can look terribly naff and crude.’

Digital Craft, published by Lee 3D, can be purchased here.