During the LPBF process, the part is subjected to continual heating and cooling cycles. This so-called thermal history touches every aspect of the part’s quality, from its microstructure, defects, geometric fealty, surface integrity, residual stresses and build risk, and ultimately, determines its functional properties, such as strength and fatigue life.

The thermal history is a complex physical phenomenon governed by the shape of the part, processing parameters (laser power, scan velocity), machine environment (gas flow, laser focus), feedstock material properties, part orientation and supports, build conditions (number of parts, time between recoat), and stochastic effects. Any change in these factors will modify the thermal history and part properties.

The current practice for LPBF process qualification relies on an empirical build- and-break approach. Simple shapes in the form of small cubes, cylinders and mechanical test coupons are built under different processing conditions, with the microstructure and metallurgical aspects of the parts characterised with X-ray CT, optical and electron microscopy, and mechanically tested. Once these coupon tests are completed, the optimal processing parameters are used for building functional parts. Alas, practitioners have found that the processing parameters optimised from simple coupon shapes seldom transfer nor scale to complex parts, which necessitates further rounds of build- and-break tests. All in, the build-and-break approach may cost several million dollars and years of engineering effort. Surely, there must be a smarter, faster, and more affordable path toward rapid part quality qualification?

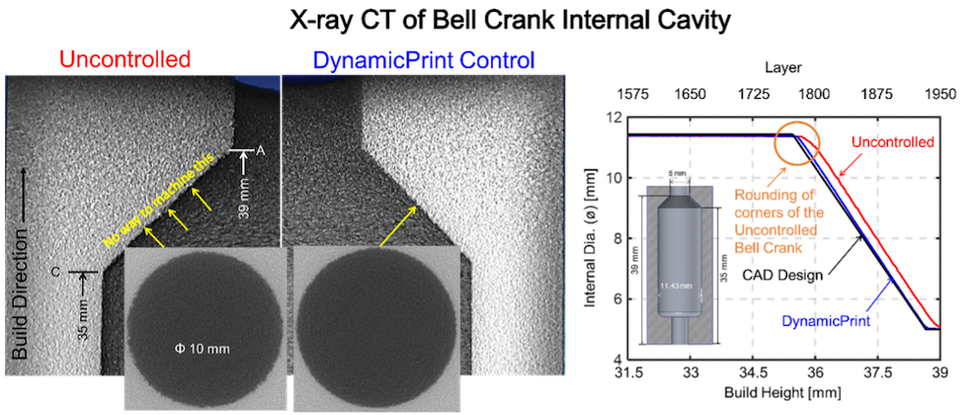

The answer lies in understanding the fundamental thermal physics of why coupon optimised parameters fail to scale. Even when built under identical conditions, the thermal history of a test coupon is markedly different from that of a complex impeller part. Ergo, the microstructure and properties of the two will differ radically. To complicate matters further, the cross-section of a complex part, and consequently, its thermal history will change between layers resulting in anisotropic, inhomogeneous properties. For example, a 41 mm tall stainless steel 316L bell crank part that tends to accumulate heat in the latter layers due to poor thermal conductivity of the powder will see its bottom layers cool more rapidly compared to the top layers, as the build plate absorbs heat faster. Indeed, LPBF practitioners innately know that maintaining constant processing parameters across all layers is a recipe for sadness.

The solution to rapid part quality qualification and achieving consistent part quality lies not in optimising the processing parameters, but tightly controlling its thermal history. With this basic concept in mind my research group at Virginia Tech developed and implemented an approach called DynamicPrint which adjusts the processing parameters layer-by-layer to maintain a consistent thermal history and reduce variation in part properties. The secret sauce in DynamicPrint is a patented mesh-free graph theory computational thermal simulation model that is about ten times faster than non-commercial finite element approaches, and has been experimentally validated to predict the thermal history within 5% error.

Get your FREE print subscription to TCT Magazine.

Exhibit at the UK's definitive and most influential 3D printing and additive manufacturing event, TCT 3Sixty.

DynamicPrint uses the graph theory thermal model to war-game the effect of changing process parameters layer-by-layer on the thermal history. It then autonomously generates a layer-wise processing plan within hours before the part is printed to obtain an ideal thermal history. A form of digital feedforward model predictive control, DynamicPrint enforces process parameter boundaries set by the operator, e.g., the laser power can only be changed within certain limits.

DynamicPrint was tested with a variety of stainless steel 316L parts on an EOS 290 system at the Commonwealth Center of Advanced Manufacturing, Virginia. DynamicPrint eliminated recoater crashes, deleted supports, reduced microstructure heterogeneity, and improved surface finish and geometric integrity. For example, FIGURE 1 compares the X-ray CT cross-sections of the bell crank part produced under uncontrolled (constant parameter) conditions and DynamicPrint. Bottom line – for rapid qualification of LPBF parts it is essential to understand, observe, predict, and control the thermal history. This research was supported by the NSF, NIST, and DoD.

Click here to read the full study or contact prahalad@vt.edu.