The use of 3D printing in the construction industry was once considered a bit of a gimmick. A decade ago, barely a week would go by without an announcement regarding a first 3D printed house, hotel, office - even a castle. Today, it has found itself a suitable niche in providing compact housing solutions, which can be rapidly built where needed, and in modular or complex structures - such as bridges and sculptures - that traditional methods would find either challenging or impossible to deliver. Just this week, for example, we reported on the completion of Japan's first government-approved two-story 3D printed reinforced concrete house - the benefit, makers COBOD International believe, is the ability of 3D printed reinforced concrete to serve as a 'structural alternative to timber construction in one of the world’s most earthquake-prone regions.'

Today, a new research project at the RWTH Aachen University Chair Digital Additive Production (DAP) aims to take another leap, by not only using 3D printing to build, but to take waste from the construction industry and repurpose it as printing feedstock.

The UN Global Construction Report 2024/25 claims over a third of global energy-related CO₂ emissions and 32% of worldwide energy consumption comes from the construction sector. This BMWE-funded research project - called Additive Manufacturing of 3D Connection Elements in Construction (AddMamBa) - plans to explore if CO₂ emissions and resource consumption from the sector could be significantly reduced by using recycled steel to build reusable 3D printed facade brackets.

The project focuses on building facade brackets for ventilated facade systems (VHF) and connectors for load-bearing structures, using laser-based powder bed fusion and metal powder derived from steel scrap. The scrap is first sorted and analysed according to its condition and chemical composition and then undergoes a gas atomisation (VIGA) process to create the powder, which is then sieved to deliver a particle size fraction of 15-45 micrometres, ready for printing.

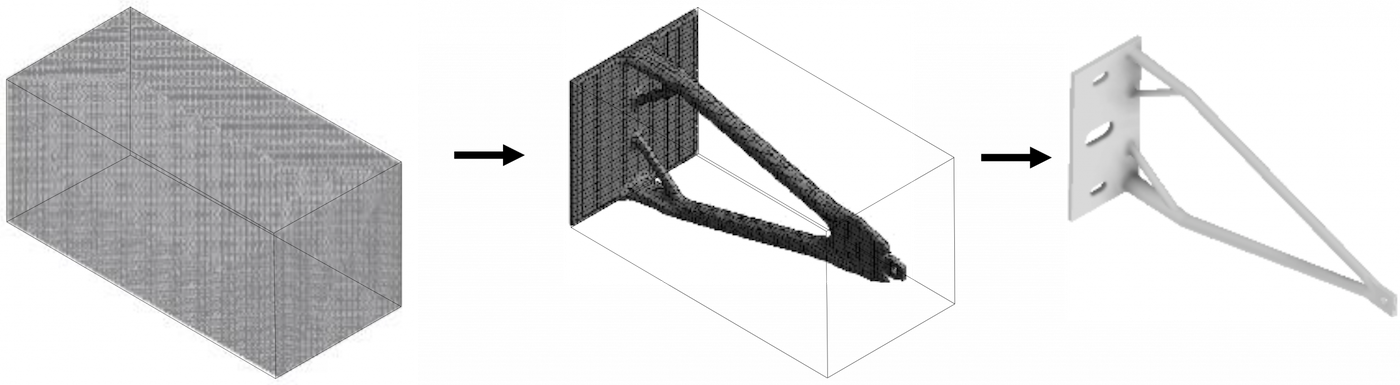

3D printing allows facade connections to be designed without the need for tools or moulding, and adapted for required building geometries. The researchers are also employing topology optimisation to enable load-path-oriented material distribution. A digital planning tool has also been developed to help with selecting suitable bracket solutions based on building and facade data, and substructure configuration. It also takes into account relevant standards, in particular DIN EN 1991-1-4/NA.

The project is designed to be circular, meaning components can be demounted and reused. Initial Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) calculations based on conservative electricity-mix scenarios suggest a Global Warming Potential of 23.8 to 33.5 kg CO₂ equivalents per kilogram of component (2030), with a further downward trend expected due to the increasing share of renewable energy sources. The analysis also shows that offsetting the higher manufacturing-related emissions through operational savings is most effective in buildings with conventional gas heating systems, but less so when combined with modern heat pump systems. This finding, according to the researchers, emphasises the importance of the circular economy aspect of the project. In experimental trials, approximately 60% usable metal powder was recovered from the processed steel scrap (30 kg of powder from 50 kg of scrap).

In a press release, the researchers said the project 'establishes a concrete application pathway for making secondary materials usable within the AM process chain' and 'unlocks the potential to convert steel scrap into high-quality components, thereby helping to close material loops in the construction sector.'